Puglia, which extends from the “spur” to the “heel” of Italy, provides ample reason to visit this less touristed part of the country: history that predates the ancient Greeks, art of the medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods, lush landscapes and gentle seashores, consistently delightful weather, and a cuisine that conquers all appetites.

Although five million travelers from the United States flock to Italy annually, less than one percent of them—35,000—visited Puglia last year, up from 27,000 two years before. Others have discovered Puglia to a greater degree, as Americans account for only six percent of all international arrivals. Puglia, however, offers plenty of four- and five-star hotels, which Americans tend to prefer. In addition, a wide range of comfortable three-star properties and numerous B&Bs abound in the towns and cities, while farms and country villas readily accommodate a growing agro-tourism clientele.

Given its strategic location—bounded by the Adriatic Sea on the east and the Ionian Sea on the south—Puglia is rich in history. The Greeks first settled there in the eighth century BC before the Romans conquered it about five hundred years later. After the fall of Rome, the Byzantines settled in for five centuries years until the Normans came in the 1200s. Two centuries later, Puglia was absorbed into the Kingdom of Naples and then taken over, successively, by the Turks, Austrians, and French until it became part of a united Italy in 1861.

So, yes, Puglia (Apulia in Italian) is used to visitors from abroad. Perhaps because the region doesn’t receive as many tourists as other parts of Italy (though it boasts two UNESCO World Heritage Sites), or perhaps because the warmer southern climate encourages a more relaxed pace, Puglians welcome you with an especially warm and engaging friendliness that is often accompanied with an invitation to eat and drink.

One can tour Puglia by train or bus, but a car provides more flexibility to explore byways and niches not easily reached by public transportation. The following north-to-south itinerary provides a good introduction to this enticing corner of Italy.

Driving through the littoral of Molise, a white lettered, green highway sign proclaims “Puglia,” telling you that you’ve arrived in the easternmost of Italy’s 21 regions. You’re in the Gargano Promontory, the “spur” on Italy’s east coast. To your left is the Adriatic presenting a mix of multi-hued blue streaks that recede into a white haze, and on the right are semi-parched lowlands punctuated by cows grazing in twos and threes.

Subtly, the landscape changes, becoming more lush and hinting at the pending drama of the aptly named Foresta Umbra (Forest of Shadows) that covers much of the Promontory. The interior of the forest is darkened, even in midday, by the tall descendants of ancient pines, beeches, and oaks.

Vieste, a busy town of 13,000 that juts into the Adriatic is a good first destination. June, with temperatures in the low 80s and the height of the European vacation season two months away, is a preferred time to visit. The old town is a warren of alleys filled with shops and restaurants that leads up to a cliff. To settle in, consider a late afternoon swim followed by dinner, perhaps grilled prawns with a local Malvasia white wine, at an open-air restaurant on the town’s high ridge overlooking the town and sea.

The roads that cut through and ring Gargano National Park, which comprises a good part of the Promontory, traverse the only mountains (up to 3,500 feet) of Puglia. Driving is safe; one can’t pick up speed because the next switchback turn is almost always immediately in front of you. Distances are relatively short within the Promontory, but the slow going means its better to move on to the next town instead of using one as a base to explore the area. Before heading to to Trani, about halfway to Bari, capital of Puglia, stop first at Monte Sant’Angelo, perched atop Mount Gargano.

Popular as a day trip, Monte Sant’Angelo is home to the thirteenth century Sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo, one of seven groups of buildings that comprise a UNESCO World Heritage site. It’s at the Sanctuary in 490 A.D. that the Archangel Michael supposedly first visited, offering the local Christian population protection from pagan warriors. In a grotto deep inside the building, accessible by an internal stairway that’s flanked by walls strewn with graffiti left by visiting pilgrims over the centuries, is a stone outcropping where Michael is said to have left a footprint. The Sanctuary remains an important pilgrimage site today.

About four times the size of Vieste, Trani served as an embarkation point for the Crusades and, until the thirteenth century, was home to southern Italy’s largest Jewish community. Today, only one of four original synagogues, the Scolanova, remains. Nearby is Trani’s cathedral, dating from the twelfth century. Sited unusually at the edge of town, as opposed to the center, and nearly up against the sea wall, the cathedral and its tall bell tower helped guide sailors to port. To fully appreciate how the bell tower may have served as a beacon, visit it at night when its white façade, lit up, stands dramatically against the dark blue sky. A few hundred feet away is the equally impressive, nearly complete remains of a Swabian castle. Its blocky design is suggestive of twentieth century modernist architecture, although it was constructed in the thirteenth by Frederick II, Holy Roman emperor and Crusader who built prolifically throughout Puglia.

In the town’s port nearby, the local fishing fleet moors comfortably cheek by jowl with pleasure craft. A generous pedestrian sidewalk forms a U-shaped perimeter around the port, inviting a lively passeggiata (evening stroll). As fisherman hawk their daily catch, locals and tourists walk and chat, and catch a glass of Prosecco (sparkling wine) or dinner at one of the many restaurants that overlook the port. Seafood—including mussels, bass, and mullet—dominates the menu, but not exclusively. Pasta also rules here – in the form of orecchiette (small shells) and maccheroni (straight, curved, or hollow). Not surprisingly, olives and wine are plentiful—in bold as well as subtle varieties—since Puglia is Italy’s largest olive and wine producer.

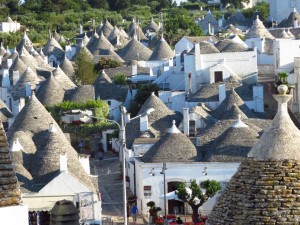

The next morning, following a light breakfast of cappuccino and cornetti (the Italian version of croissants), it’s back on the coastal road toward Alberobello, a must-see UNESCO World Heritage site. Slightly smaller than Vieste, Alberobello is known for its trulli, whitewashed stone, hut-like structures topped by cone shaped roofs that were used by fieldworkers over the past three centuries. Today, following restoration, they serve as homes and businesses. Some have been converted into bed-and-breakfast accommodations that offer ultra modern conveniences and finishes, making for a comfortable overnight stay. The several hundred remaining trulli are concentrated on the town’s two hills, one comprising a residential area and the other focused on the tourist trade. Striking because they are unusual, the trulli quickly become become part of your visual landscape, all the more so as you encounter local residents in the streets and children playing in the local piazzas.

Next stop: Lecce, located on the Salento peninsula, which forms the end of the “heel” of Italy. Sometimes referred to as the Florence of the South, due to the profusion of Baroque architecture and more than three dozen churches, Lecce is large enough to offer the sophisticated diversions of urban life, including concerts, galleries, and boutiques, yet small enough to be traversed on foot. Like all Puglian towns and cities, Lecce takes a siesta during the warm afternoon hours. But afterward—in the grand Piazza Sant’Oronzo, which borders the remains of a second century, 15,000-seat Roman amphitheater, as well as in many café-and-restaurant-filled side streets—life explodes anew as the passeggiata arrives.

Eating in Lecce is similar to dining elsewhere in Puglia: the food tends to be very good or excellent – and always satisfying and memorable. For example, there’s prosciutto with melon or mozzarella; pasta with squid, cherry tomatoes, and toasted bread crumbs; orecchiette with mussels, Salentine cheese, or pork sausage and mushrooms; strascinate (similar to orecchiette) with sweet peppers and anchovies; tuna tartare; filet of beef with olive oil and grilled vegetables; or perhaps grilled gamberoni (prawns). Vegetarians are easily satisfied in Puglia (as elsewhere in Italy), because every menu offers a variety of local vegetable dishes that may include zucchini, eggplant, peppers, beans, chickpeas, or tomatoes, prepared with a variety of wine, cheese, and other sauces, as well as caprese salad (sliced mozzarella, tomatoes, and basil). Nearly all vegetables are fresh, but restaurant menus will advise if frozen product is used.

Given that the Salento peninsula juts into the Adriatic and Ionian waters, it makes sense to take a seaside break in Otranto, a charming, small town of 5,500 located at the bottom of Italy’s “heel” just a few miles from the country’s most easterly point. On a clear day, looking due east it’s possible to see Albania. Upon cresting a small hill on the SS16 highway approaching Otranto, a veritable forest of olive trees spreads before you. A few minutes later, as you wend your way through the town, you find yourself at the edge of the deep turquoise-colored Strait of Otranto, which divides the two seas.

An important harbor in Greek and Roman times, Otranto served as a launching point for sailors headed for the Orient. It later fell to Byzantine rule before the Normans conquered the area in the eleventh century. After taking over the town in 1480, the Turks infamously beheaded 800 Catholics who wouldn’t convert to Islam. The old town’s center today is ringed by a thick, defensive wall that is part of the surviving Aragonese Castle. The town’s eleventh century Norman cathedral with its elaborate mosaic floor that depicts a tree of life growing from the backs of two elephants, is unique, as is the collection of skulls and bones of some of the martyred Catholics neatly stacked in an apse nearby. A few narrow streets away, the tiny Chiesa di San Pietro, thought to once have been the primary church of Otranto, features stunning Byzantine frescoes.

A busy beachfront promenade features drink and snack—even cotton candy(!)—vendors, along with an array of excellent seafood restaurants, making it easy to unwind. Cafés along the Villa Comunale, a small park near the city walls, overlooking the harbor, offers a front row seat of the daily passeggiata.

Otranto has several sandy beaches, conveniently located near the town‘s center. If they prove too crowded, more likely to be the case during the height of the summer, a number of fine beach spots are accessible at Baia dei Turchi just north of Otranto and at Porto Badisco to the south.

Having reached the southern end of Puglia, you may think you’ve come to the end of your visit to this seductive land. However, make an effort to visit Matera, inland and just west of the “arch” of the Italian “heel.” Located in the region of Basilicata, Matera until the seventeenth century had been part of Puglia, the border of which is about six miles away.

Settlers first arrived in Matera about 9,000 years ago and today the city is best known for its Sassi di Matera (stones of Matera) – stone dwellings carved into the rock, first built in the 1700s. The Sassi, of which hundreds exist in two clusters called Sassi Barisano and Sassi Caveoso, became overcrowded in the nineteenth century, leading to high poverty, malaria, and infant mortality rates. A mandatory relocation of residents in 1952 led to the abandonment of the Sassi. Starting in the late 1980s, however, the government encouraged investment and renovations. Today, the community is thriving once again; a number of Sassi have been converted into modern B&Bs, providing unique half-cave, half-contemporary rooms, complete with full bath, air conditioning, and wi-fi.

The Sassi have been named a UNESCO World Heritage site and are the primary reason tourists visit Matera. Don’t miss the old town’s historic and extensive water collection system and cave churches carved from rock, later used for making and storing wine, that still display 1000-year-old frescoes on interior walls. You can explore the Sassi on your own, but hiring a guide is worth the effort for a more profound history lesson and entrance into sites that are not easily accessible.

Currently, Matera is vying to be Italy’s European Capital of Culture 2019—seeking to go “from stalls to stars,” as the locals say—and in the third quarter of 2014 a judging panel will decide which of six Italian cities (including Lecce) will get the nod.

Puglia Tourism, www.viaggiareinpuglia.it